An opportunity to play tennis at Rutgers led Alister Martin to a career in medicine and public policy—and the chance to shape both as a White House Fellow.

Alister Martin’s journey from high school to the White House began in his senior year after a fight with members of a street gang in his neighborhood. It left him with two broken wrists, a fractured facial bone, and a rude awakening. The fact that Martin RC’10 wasn’t aware of the fighters’ affiliation was immaterial: Neptune High, in a Jersey Shore town plagued by gang violence, had a zero-tolerance policy toward gang activity. The school expelled Martin, propelling him, he says, to “rock bottom.”

With that stain on his record, no local school would take him. And, as the cops told his mother, his tussle with gang members meant he wasn’t safe in town, which is how he found himself at the Nick Bollettieri Tennis Academy in Bradenton, Florida. Martin’s eighth-grade teacher had gotten him a summer job sweeping up at a local tennis club and he’d fallen hard for the sport; four years later, he showed real promise. His mother, who secured a $15,000 loan to pay his academy tuition, saw tennis as a potential life raft for a young Black man adrift in perilous seas. And she was right.

Safety net

Tennis—along with Martin’s innate resilience, persistence, and intelligence—changed his trajectory. He was recruited by Rutgers’ assistant tennis coach Bob Stanicki, who helped him earn his GED, and in September 2006, Martin stepped onto the New Brunswick campus, elated. “I could’ve died right there,” he says. “I had an opportunity to swing for the fences.”

Martin was also terrified. He had never applied himself academically and he had no idea if he could. Then he learned about Rutgers’ Office for Diversity and Academic Success in the Sciences (ODASIS), a program that offers minority students guidance and supplemental academic instruction.

Discovering ODASIS, says Martin, “was like finding a light switch in a dark room,” illuminating a path to his long-held dream of going into medicine. That dream was kindled when he was 11, after his mother, who had raised him alone, was treated for metastatic breast cancer. Against the odds, she survived. The doctors who saved her, he says, “were the closest thing I’d seen to real-life superheroes.” After four years at Rutgers—“the most important thing that ever happened to me,” Martin says—he was on his way to joining their ranks, at Harvard Medical School.

Born to care

It was almost preordained that Martin would study emergency medicine. Growing up on the edge of poverty—his mother was a biology teacher who worked several jobs to keep the two of them from falling off that edge—he knew that in some underresourced communities, the ER was a kind of medical Ellis Island, the place everyone passes through. If you want to understand the community you serve and if you’re inclined, as Martin was, to solve the problems posed by “failed health care policy,” there’s no better place to be than the emergency department.

That desire to cure not just his patients but also the system that served them, often poorly, compelled him to pursue a master’s degree in public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School. As a third-year medical student, he had already witnessed what he calls “the sometimes barbaric nature of our health care system.” He asked himself, “Do I complain about this my entire career? Or do I try to figure out how I can be part of the solution?” It should surprise no one that a man for whom clinical medicine and public service are inextricable would choose the latter.

Emergency preparedness

At Massachusetts General Hospital, where he later became chief resident, Martin encountered an opioid-addicted patient who had come to the ER for help, but he discovered he couldn’t prescribe the anti-addiction drug buprenorphine without first securing a Drug Enforcement Agency waiver. In response, Martin founded Get Waivered, a campaign to encourage ER physicians to apply for the waiver.

He also founded the VotER campaign, through which ER doctors help patients register to vote, and cofounded GOTVax, a COVID-19 vaccination program sponsoring pop-up clinics throughout Boston. All three campaigns, he says, allowed him “to use the emergency department as a place to serve the needs of vulnerable patients.”

A view from the top

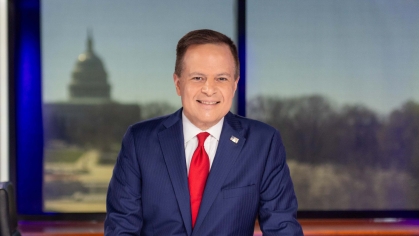

This year, Martin is fulfilling a desire to serve those patients from the world’s most elevated vantage point as part of the 2021–2022 class of White House Fellows. Each year, this select group of professionals is chosen from diverse disciplines to work directly with White House staff, cabinet secretaries, and senior officials. Martin is now working with Vice President Kamala Harris as a senior advisor on voting rights and the Office of Public Engagement to bring health insurance to the uninsured.

His plans post-White House aren’t fully formed, but he already knows what he wants to do: “to continue this combination of clinical care and social entrepreneurship—starting programs and interventions and trying to think outside the box when it comes to addressing problems in health care.”

That he’s been doing this since his first day at Rutgers bodes well for Martin—and for the nation of patients he aims to serve.